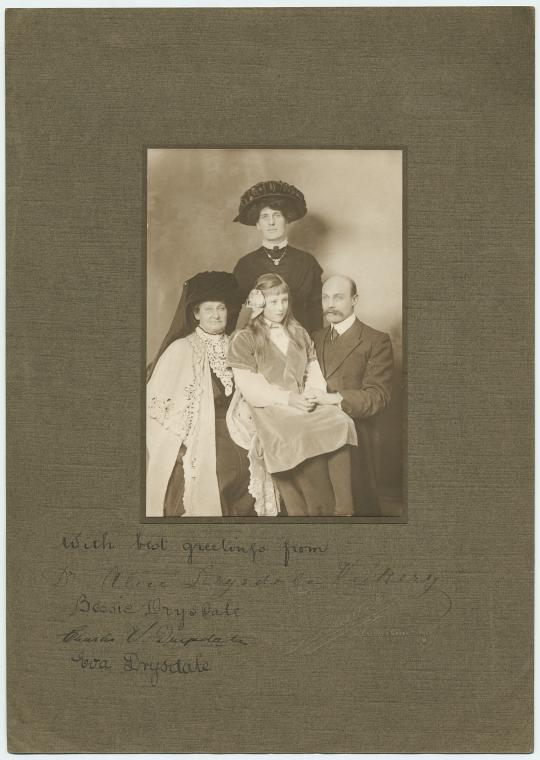

Moncure and Ellen Conway

Ellen Dana (1833–1897) and Moncure Daniel Conway (1832–1907) married on 1 June 1858, with a bridal party which included the brother of poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Theirs would be a mutually supportive and devoted marriage, and one which would help to shape the story of today’s Conway Hall Ethical Society.

At home in America, the abolitionist couple were co-conspirators in transporting 31 enslaved people from Virginia to freedom in the North. In 1863, it was Moncure Conway’s abolitionism which brought him to London’s South Place, where he was subsequently invited to become ‘minister’. Under his leadership–and with Ellen’s close collaboration–what was then still a ‘religious’ society became increasingly humanist, and Moncure a self-proclaimed freethinker. Although today’s Conway Hall would be named, in 1929, after Moncure, it’s clear that the couple were mutually influential. On Ellen’s death in 1897, one member wrote that ‘much of the best work at South Place originated from her’.