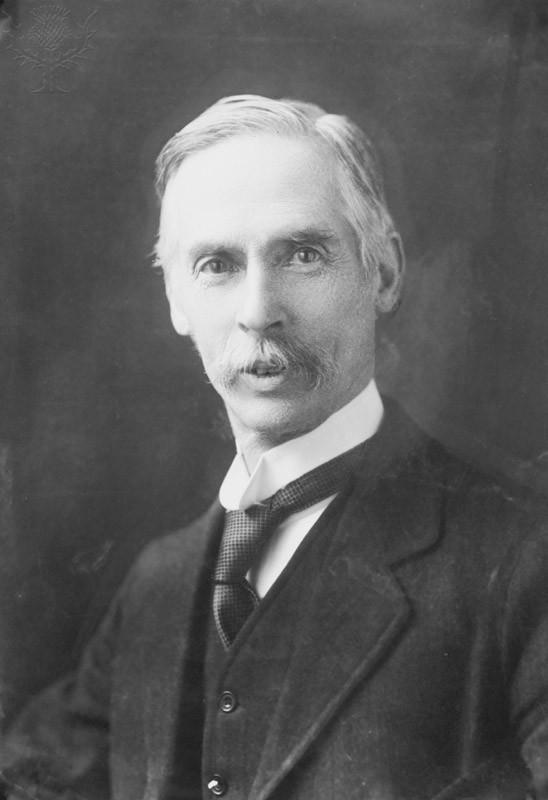

The position of President was only formally created by the Union of Ethical Societies (now Humanists UK) in 1918, when Dr. John Stuart MacKenzie was awarded the honour. The Union of Ethical Societies had, however, been in existence since 1896, and in that time many prominent figures had been actively associated with it, including as Chair of its Council and Annual Congress, and as President of individual societies. These included first editor of the Dictionary of National Biography (and father of Virginia Woolf) Leslie Stephen, and first Labour Prime Minister James Ramsay MacDonald, as well as a number of remarkable women, such as activist Elizabeth Swann and feminist writer Zona Vallance.

In the same year as the role of President was created, a selection of Vice Presidents were elected. This original group included secularist and peace activist Hypatia Bradlaugh Bonner, pioneer of moral education F.J. Gould, and educationist and suffragist Millicent MacKenzie. Later Vice Presidents included novelist E.M. Forster, psychologist Margaret Knight, and philosopher Bertrand Russell, among many others.

Humanists UK began as the Union of Ethical Societies in 1896, becoming the Ethical Union in 1920, the British Humanist Association in 1967, and Humanists UK in 2017. These name changes are reflected in the descriptions for each of the Presidents on this page.

The way to save ourselves from being dazzled by the new light of thought is not to bury ourselves in the darkness, but rather to live steadily, from the first, in the open sunshine.

J.S. MacKenzie in The International Journal of Ethics, 1908

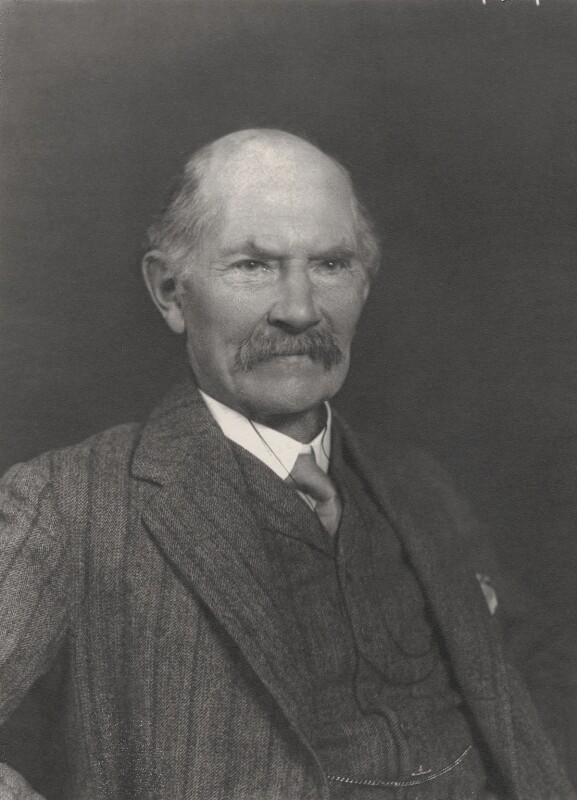

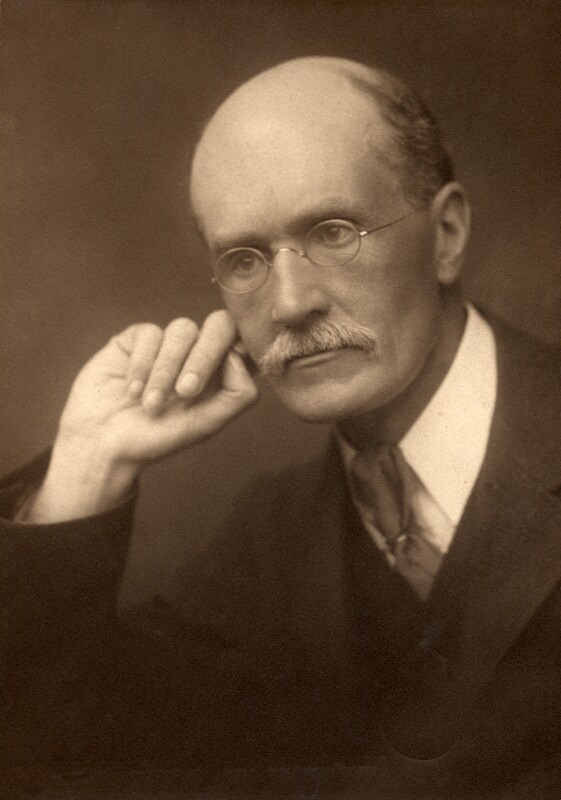

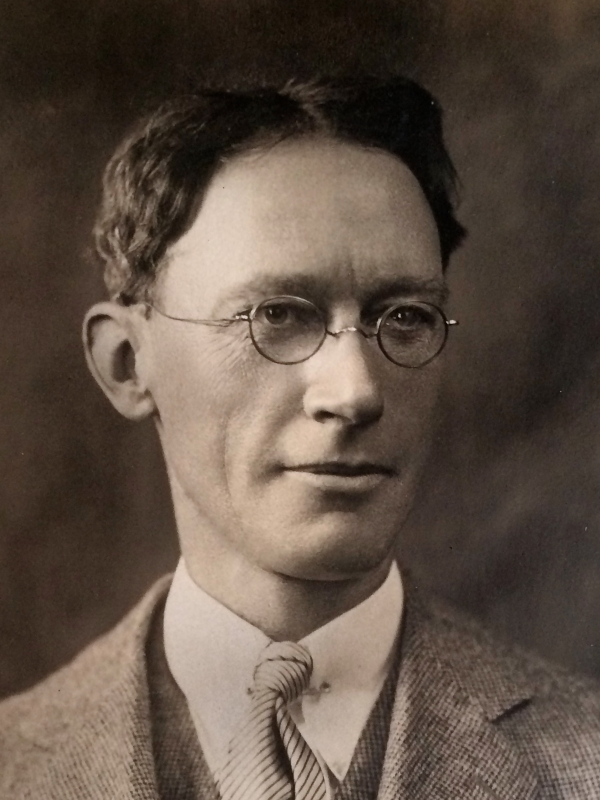

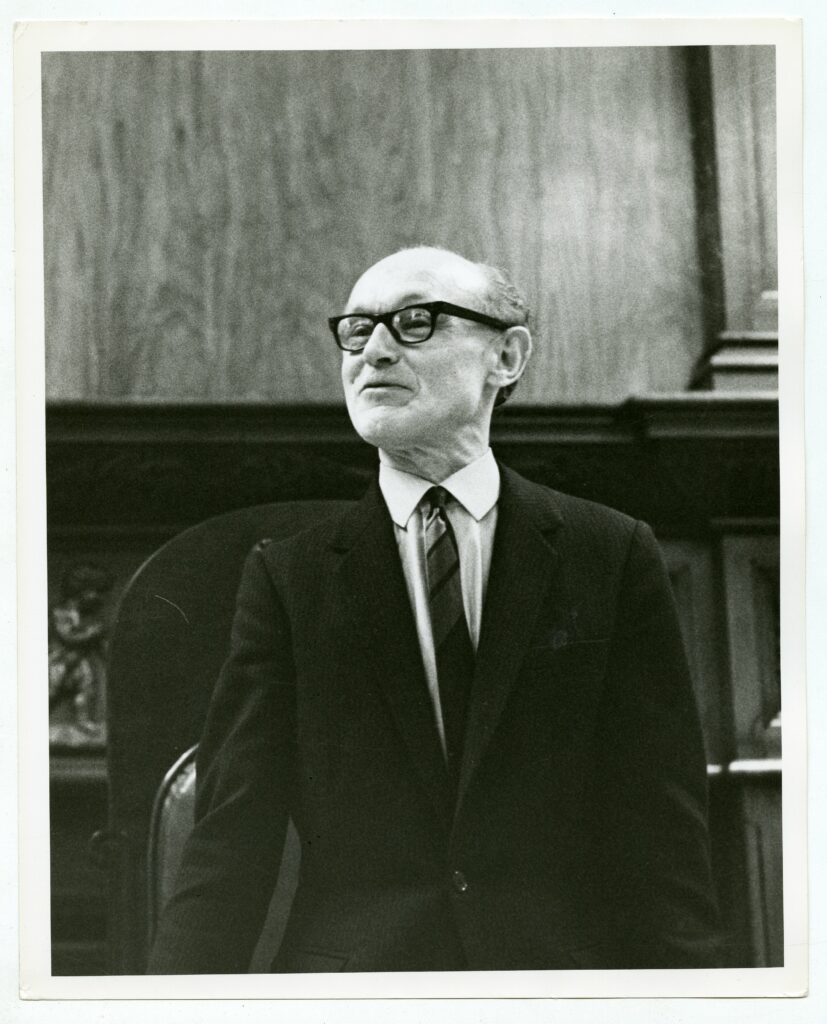

John Stuart Mackenzie (1860–1935), philosopher.

J.S. Mackenzie was a philosopher and longtime supporter of the Ethical movement, who published Lectures on Humanism in 1907, ‘at a time’, he wrote, ‘when the importance of philosophical principles in the general life of mankind [was] becoming more and more apparent’. This idea of applying philosophy and ethical ideals to practical efforts at living well was central to the early humanist movement. Mackenzie was also President of the Moral Education League 1908-1916.

Recording the appointment of Mackenzie as its inaugural President, the report of the Union of Ethical Societies noted:

[The Council] was fortunate in being able to secure as the Union’s first President Dr. J.S. Mackenzie, M.A., whose connection with the Ethical Movement has lasted for more than thirty years; his ripe judgement and scholarship have already been of the greatest service to the Council in the conduct of its work.

Twenty-fifth Annual Report of the Union of Ethical Societies (1919)

See also: Mackenzie Hall and Millicent Mackenzie.

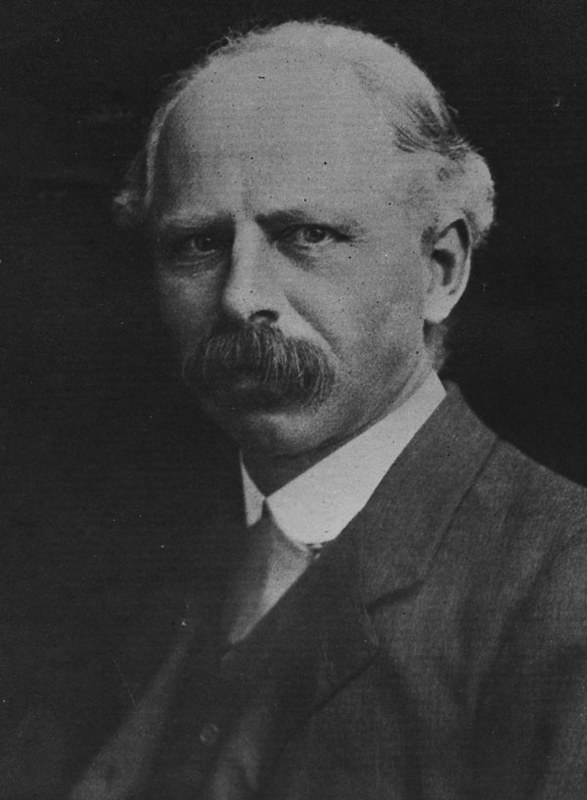

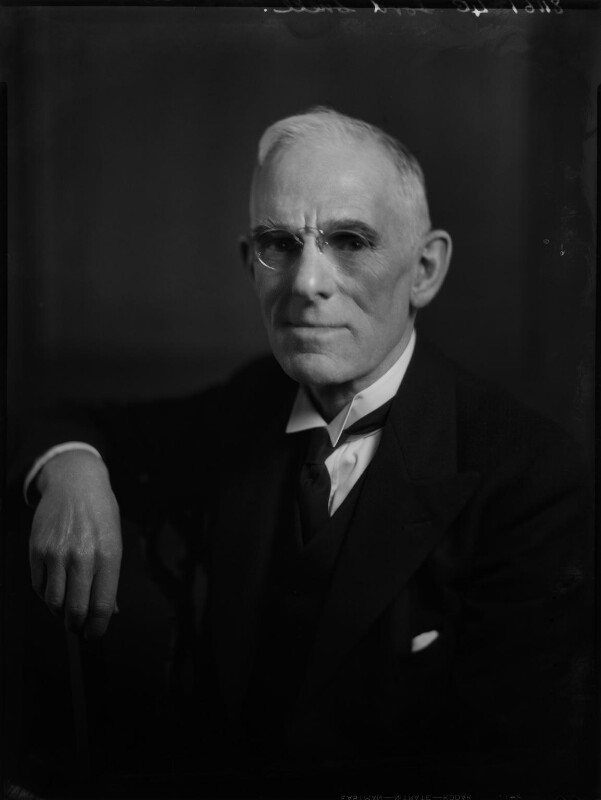

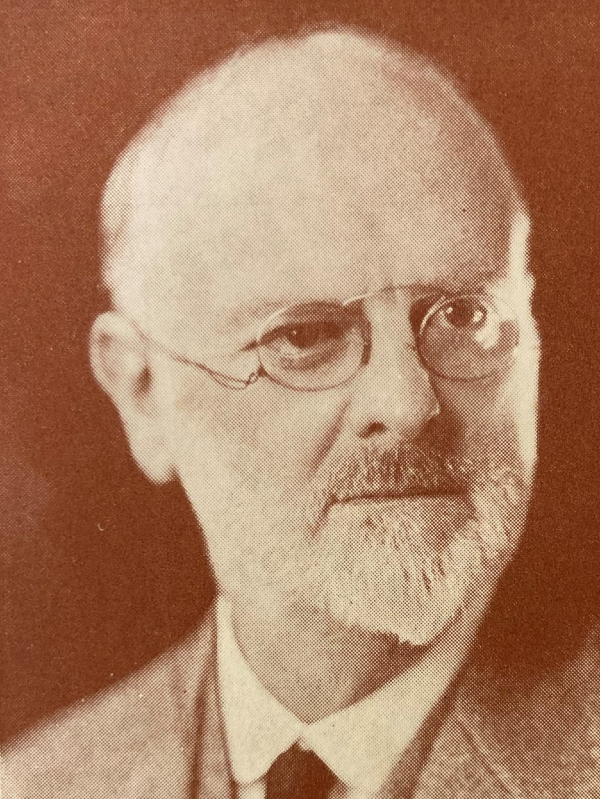

John Atkinson Hobson (1858–1940), social theorist and economist.

Good character and conduct derive their value and authority not from any supernatural or external source, but from their inherent virtue and appeal. The human reason is the proper instrument for the discovery and application of the principles and rules of a good life. The social nature of man makes it serviceable for seekers after this rational good to help one another by organised co-operation, and to win from this communion a clearer inspiration and a firmer purpose.

J.A. Hobson, ‘ ‘The Ethical Movement and the Natural Man’ in The Hibbert Journal, 1922

John Atkinson Hobson was an early member of the Ethical movement, joining the London Ethical Society in 1890, and South Place Ethical Society in 1895. He became an Appointed Lecturer at South Place in 1899, remaining one until 1934. Along with James Ramsay MacDonald and J.M. Robertson, Hobson was a member of London discussion group the Rainbow Circle from its inception in 1894, alongside many other progressive thinkers and social activists. He co-edited the Ethical World 1899-1900, and in 1922 wrote ‘The Ethical Movement and the Natural Man’.

Our concern is with conduct, not with worship, and however inseparable these are in popular thought, it is clear that they are separable in practice.

J.H. Muirhead, ‘The Position of an Ethical Society’ in Ethics and Religion (1900)

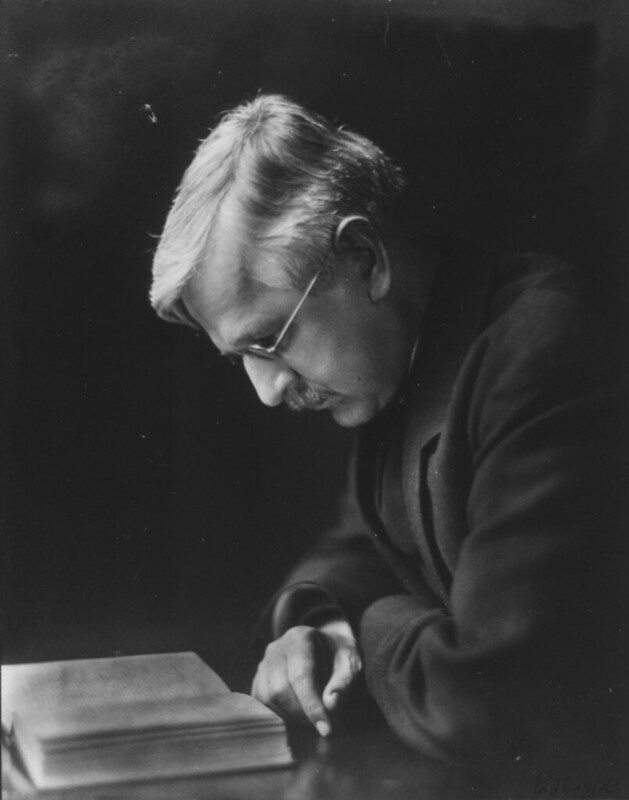

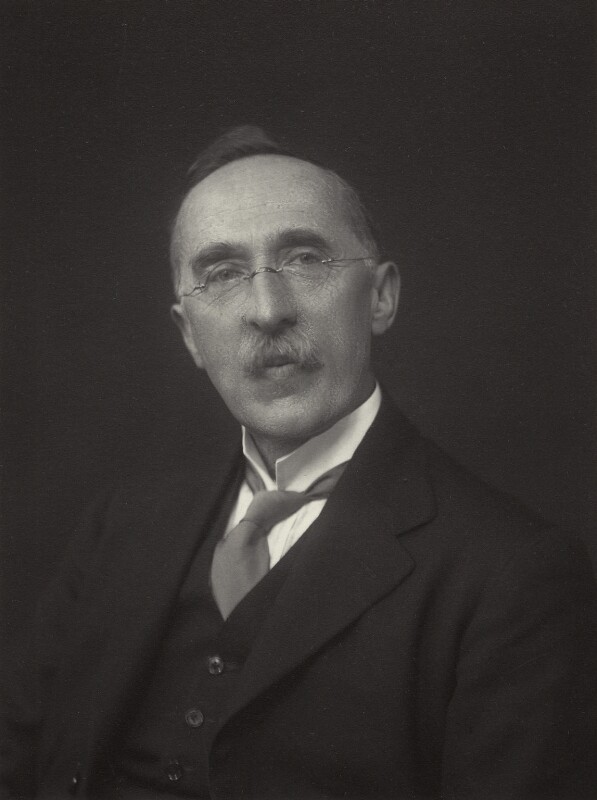

John Henry Muirhead (1855–1940), philosopher.

Muirhead was a leading figure in the formation of the London Ethical Society, the UK’s first, in 1886. He was influenced in his thinking by the practical philosophy advocated by figures such as T.H. Green (under whom he studied), and J.S. Mackenzie, the Union’s first President. In 1918, with H.J.W. Hetherington, he published Social Purpose: a Contribution to a Philosophy of Civic Society, containing references to a remarkable number of fellow thinkers involved in the Ethical movement. Among them: Bernard Bosanquet, J.S. Mackenzie, T.H. Green, Bertrand Russell, L.T. Hobhouse, H.N. Brailsford, and Graham Wallas. Muirhead’s first wife, Mary Talbot Wallas, was the sister of Graham Wallas, who became President of the Union in 1924. Like Muirhead’s forerunners in the role of President, his central belief was that:

Goodness does not consist in obedience to the decrees of a supernatural Ruler of the world, but is the word for that conformity to social claims which nature imposes as the condition of the survival and well-being of a community.

‘The Position of an Ethical Society’ in Ethics and Religion (1900)

Leonard Trelawny Hobhouse (1864–1929), social philosopher and journalist.

Hobhouse, like a number of other figures in the early organised humanist movement, was influenced by thinkers such as Herbert Spencer, Giuseppe Mazzini, and John Stuart Mill, combining evolutionary ideas with theories of co-operation and the common good. He was an outspoken critic of British imperialism, and of eugenics; a supporter of women’s suffrage, and the introduction of old age pensions. He was Chair of Sociology at the London School of Economics (LSE) from 1907 until his death in 1929. His sister, Emily Hobhouse, was an activist, reformer, and charity worker. Although Emily Hobhouse was not directly involved in the Ethical movement, her sympathies appear to have been – like those of her brother – broadly humanist. In 1924, L.T. Hobhouse described ‘certain convictions’ which he believed to ‘form the fixed points of any rational philosophy’:

The first of these is the conviction of goodness — goodness neither laid up in heaven nor moving as a metaphysical principle upon earth, but warm and real in the hearts of living men and women.

L.T. Hobhouse, ‘The Philosophy of Development’ in Contemporary British Philosophy: Personal Statements (1924)

…I urge that we should read psychology, and bow ourselves before the ascertained truths that psychologists have to offer us, in the belief that some day we shall find as the acknowledged legislator of mankind a combination of the whole of man; of the best and happiest moments of the best minds; and in that combination of feeling and reason a guide for the painful struggle of mankind upon this little earth.

Graham Wallas, RPA Annual Dinner, 28 May 1923

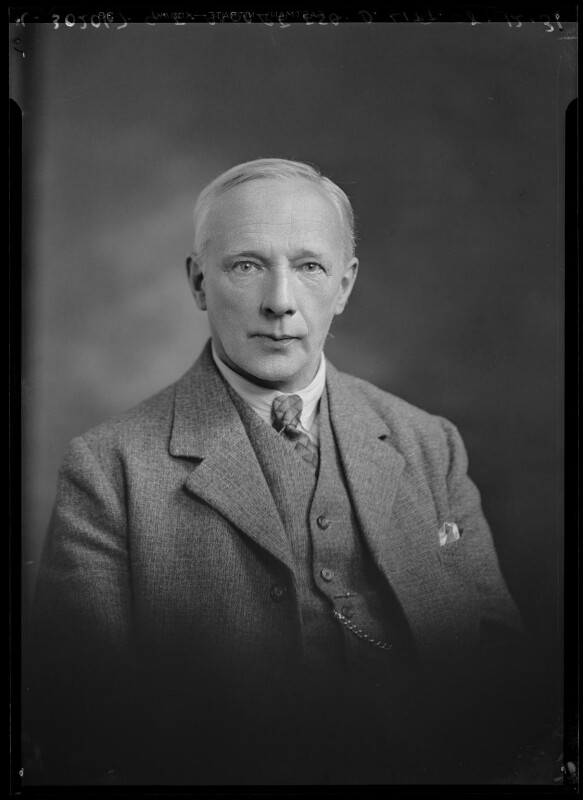

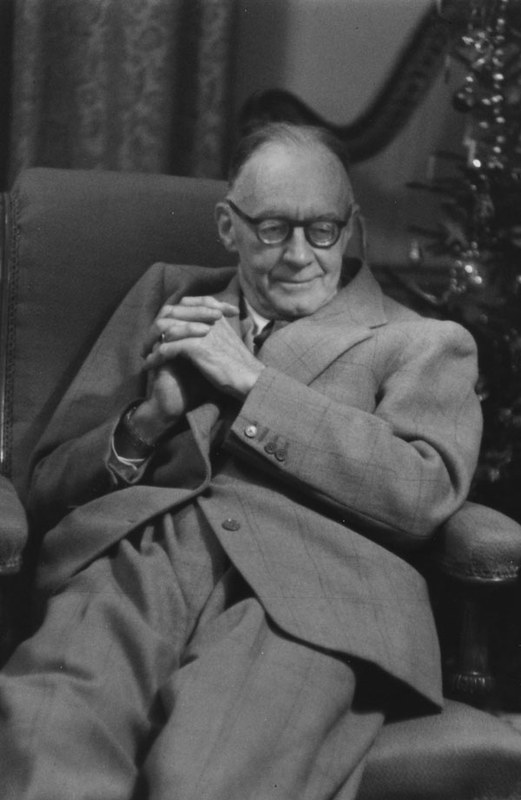

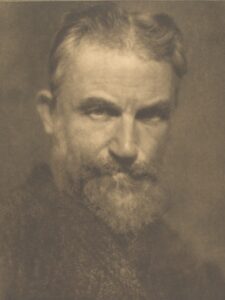

Graham Wallas (1858–1932), political psychologist and educationist.

The son of an Anglican clergyman, Graham Wallas declared himself a rationalist while at Oxford University, and from then on became actively involved with a range of progressive and humanist organisations. Close friends with George Bernard Shaw and Sidney Webb, he was a founder (with Shaw, and Sidney and Beatrice Webb) of the London School of Economics (LSE) in 1895. Made President of the Ethical Union in 1924, Wallas later became President of the Rationalist Press Association (1926-9). According to his friend and fellow humanist, Harold Laski, Wallas was:

A great teacher, a thinker of real importance, one of the most gifted talkers I have ever known, he exercised an abiding influence upon his generation. He had courage, a passion for ideas, a willingness to follow truth as he had found it wherever it might lead. Few men of our time have been so amply Rationalist as Graham Wallas.

Harold Laski on Graham Wallas in The Literary Guide, September 1932

The past speaks to us in a thousand voices, warning and comforting, animating and stirring to action. What its great thinkers have thought and written on the deepest problems of life, shall we not hear and enjoy?

Felix Adler, inaugural lecture to the New York Society for Ethical Culture, 15 May 1876

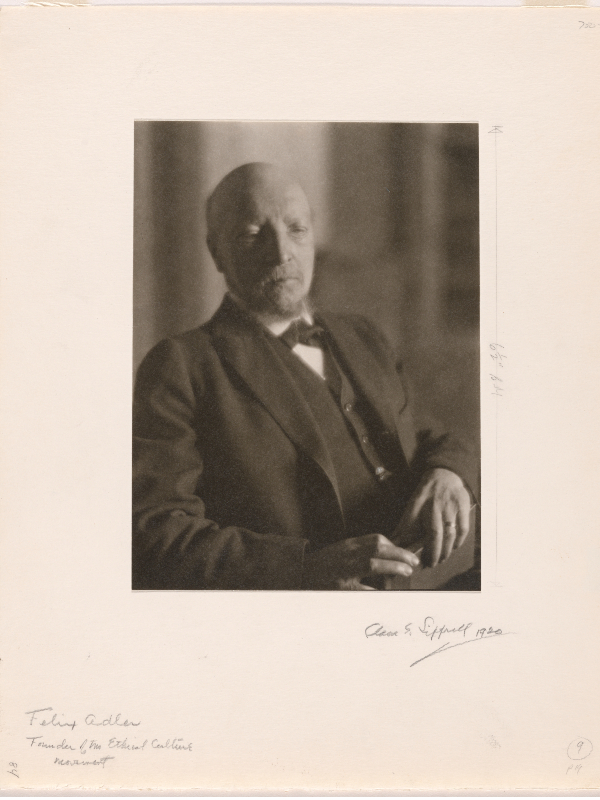

Felix Adler (1851–1933), ethicist, rationalist, social reformer.

We propose entirely to exclude prayer and every form of ritual… it is my dearest object to exalt the present movement above the strife of contending sects and parties and at once to occupy that common ground where we may all meet.

Felix Adler, inaugural lecture to the New York Society for Ethical Culture, 15 May 1876

Felix Adler was the founder of the Ethical Culture Movement in New York in 1876, and a major influence on one of the defining figures of the early humanist movement in the UK: Stanton Coit. Adler, who founded his New York Society for Ethical Culture on the basis of ‘deed, not creed’, was a dedicated social reformer in areas of education, social welfare, housing, medical care, child labour, and the rehabilitation of prisoners.

Read more about Felix Adler.

Frederick Soddy (1877–1956), chemist and social commentator.

I have, from the standpoint of an original investigator in physical science, attempted to show how fundamentally and beyond the possibility of escape our knowledge and control of the inanimate world underlies and determines the development of all the potentialities of life. Admittedly, the attempt is a very imperfect one, but scientific investigators too seldom endeavour at all to make known the bearing of their special fields of inquiry upon the general problems of life and belief.

Frederick Soddy, Science and Life: Aberdeen Addresses (1920)

Frederick Soddy was a Nobel Prize-winning chemist, whose work made significant contributions to the understanding of atomic energy. As a scientist, he was deeply concerned with the impact of research and discoveries on lived human life, and later shifted his focus to social and economic theories. On his death in 1956, Soddy left a significant bequest to found the Frederick Soddy Trust, enabling young people to travel and study the social, cultural, and economic life of other groups and regions. Biographers, such as Linda Merricks for the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, have noted that thanks to Soddy’s ‘early recognition of the dangers of atomic science’, he is today considered ‘a pioneer of responsible science’.

I feel much truth in an old Greek philosopher’s saying, ‘The helping of man by man is God.’

Gilbert Murray in This I Believe, edited by Edward P. Morgan (1953)

(George) Gilbert Aimé Murray (1866–1957), classical scholar and internationalist.

Simple kindness, simple courage, simple honesty, unassailable integrity, genuine and therefore inspiring humility – one of these qualities is enough for any man. He had them all.

A correspondent in The Times, 31 May 1957

Gilbert Murray was a classicist, peace activist, and prominent humanist, whose devotion to the literature and culture of ancient Greece animated his life and thought. In 1956, Murray told the BBC that ‘there has never been a day, I suppose, when I have failed to give thought both to the work for peace and for Hellenism. The one is a matter of life and death for all of us, the other of maintaining amid all the dust of modern industrial life our love and appreciation for the eternal values’. As well as being President of the Ethical Union, Murray was present at the inaugural World Humanist Congress in 1952, from which was formed the International Humanist and Ethical Union (now Humanists International).

Read more about Gilbert Murray.

Henry (Harry) Snell (1865–1944), politician and secularist.

[A]lthough political and Labour questions arrested my attention, and made constant demands on my time and energies, my deepest and most abiding interests were in religion and ethics, and to these great subjects that the best thought and work of my life has been given.

Harry Snell, Men, Movements and Myself (1936)

Harry Snell received only a sporadic childhood education, cut short by the call to work as a cattle minder and bird scarer at eight years old. Following a programme of self-education, evening classes, and freethought lectures, he became secretary, in 1895, to the first director of the London School of Economics, and lectured for the Fabian Society. An active and devoted humanist, Snell became organiser and lecturer for the Union of Ethical Societies in 1899, and was Secretary of the Secular Education League 1907-1931. From 1922-1931 he acted as MP for East Woolwich, and was later made Baron Snell of Plumstead, Kent. Prior to becoming President in 1931, Snell had given many years to the Ethical Union, including as Secretary and Chair of the Council.

Read more about Harry Snell.

George Peabody Gooch (1873–1968), historian, journalist, and Liberal Party MP.

Before becoming President of the Ethical Union in 1933, George Peabody Gooch had been a member of the Ethical movement for nearly four decades. Born into a wealthy family in Paddington, London, he broke with the Conservative politics of his upbringing and later became Liberal MP for Bath (1906-10). Gooch co-edited the Contemporary Review from 1911, and was its sole editor 1931-60. President of the Historical Association of Great Britain 1923-26, he was made – in the same year as becoming President of the Ethical Union – President of the National Peace Council. Gooch was an active supporter of moral education (rather than religious instruction) in schools, moving a motion in the House of Commons in 1909:

That in the opinion of this House, provision should be made, in the Code, for Moral Instruction to be effectively given in every elementary school, and that the Regulations for the Training of Teachers should be so amended as to secure that they are adequately trained to give such instruction.

In 1913, he led a deputation to the Parliamentary Secretary to the Board of Education, echoing this call.

George Edward Moore (1873–1958), philosopher.

The tremendous influence of Moore and his book on us came from the fact that they suddenly removed from our eyes an obscuring accumulation of cobwebs, and curtains, revealing for the first time to us, so it seemed, the nature of truth and reality, of good and evil and character and conduct, substituting for the religious and philosophical nightmares, delusions, hallucinations, in which Jehovah, Christ, and St. Paul, Plato, Kant, and Hegel had entangled us, the fresh air and pure light of plain common sense.

Leonard Woolf, Sowing: an autobiography of the years 1880-1904 (1960)

G.E. Moore was a philosopher and humanist, who profoundly influenced the thinking of many key members of the Bloomsbury Group. In 1894, Bertrand Russell (who met Moore at the University of Cambridge) wrote: ‘I have never felt such an extravagant admiration for anybody’. Moore’s Principia ethica, published in 1903, was a key influence on Leonard Woolf, Lytton Strachey, and John Maynard Keynes.

Read more about G.E. Moore.

Every man who is not already half dead is always thrusting out new roots into the common earth of daily custom and converse, and new shoots upwards towards poetry, music and the other arts… At least while we live let us be more than half alive.

Cecil Delisle Burns, ‘Alive, Alive-o!’ in The Monthly Record, November 1940

Cecil Delisle Burns (1879–1942), philosopher, writer, lecturer.

The greatest of all the good things derived from science is the freedom of the mind from the fears engendered by ignorance from which our forefathers suffered. Therefore the knowledge of facts and the process by which we obtained that knowledge—which is science—is essential to the good life of the individual and the community.

Cecil Delisle Burns, ‘A Note on the Main Road’ in The Monthly Record, February 1942

Born in the West Indies, Cecil Delisle Burns studied at Christ’s College, Cambridge, and began to train for the Roman Catholic priesthood in Rome. He left the Church, though, in 1908, and remained for the rest of his life a rationalist and humanist. Burns was an Appointed Lecturer at South Place Ethical Society 1918-34, and worked in the Ministry of Reconstruction, the League of Nations, the Ministry of Labour, and for the Labour Party. He lectured at Birkbeck, the University of London, the London School of Economics, and Glasgow University. On his death in 1942, the Manchester Guardian remembered Burns as a man whose ‘humour, his wide knowledge, his intense interest in life and persons, [and] his extraordinary vitality were combined with a firm grasp of principles and a philosophical outlook’.

Stanton George Coit (1857–1944), ethical leader.

Born in Columbus, Ohio, Stanton Coit would become one of the early UK humanist movement’s most influential figures. Invited by Moncure Conway to became leader of South Place in 1888, Coit oversaw its shift from a ‘religious’ to an ‘ethical’ society. In 1892, with a group of others, he founded the West London Ethical Society, and later the Moral Instruction League, as well as the Ethical movement’s newspaper, the Ethical World. Naturalised as a British subject in 1903, Coit joined the Independent Labour Party, and stood unsuccessfully for Wakefield in 1906 and 1910. He was, alongside his wife (and like his mother), a devoted suffragist.

Read more about Stanton Coit, Adela Coit, and the Leighton Hall Neighbourhood Guild.

It lies within our power, if we so desire it, to make the familiar world we inhabit more worthy of habitation by beings who aspire to be rational and are capable of love.

L. Susan Stebbing, Philosophy and the Physicists (1937)

(Lizzie) Susan Stebbing (1885–1943), philosopher.

Although the Union of Ethical Societies had, from its origins, many women in leading roles on its Council and within its membership, L. Susan Stebbing was the first woman to formally hold the title of President. Stebbing studied history at Girton College, Cambridge and obtained an MA in philosophy at the University of London, later gaining her DLitt there in 1931. Stebbing was the first woman to hold a philosophy chair in the UK. Prior to becoming President of the Ethical Union in 1941, Stebbing had been President of the Aristotelian Society (1933), and the Mind Association (1935). She was also an active supporter of the League of Nations Union, and a firm advocate of the vital importance of critical thinking – and compassion – for the wellbeing of the individual and the world.

Read more about L. Susan Stebbing.

John Laird (1887–1946), philosopher.

Curiosity, inquisitiveness even, and a reflective bent of the mind are very general attributes of human nature. Most of us believe that they ought to be cultivated; and we should consider ourselves very sadly placed if we did not, or could not, reflect upon the values of things, the aim of the business of living, the excellence of that which we are minded to do.

John Laird, A Study of Moral Theory (1926)

John Laird was born in Aberdeenshire, the son of a third-generation reverend in the Church of Scotland. A gifted and admired thinker, he excelled in study first at Edinburgh University, and then at Trinity College, Cambridge. Following stints at St Andrews University, Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia, and Queen’s University, Belfast he became a professor of moral philosophy at Aberdeen in 1924, where he remained for the rest of his life. According to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Laird was notable for his ‘unusual mingling of rugged strength with tenderness and kindliness’.

Our goal must be the good of the whole human society.

Henry Noel Brailsford, Olives of Endless Age (1928)

Henry Noel Brailsford (1873–1958), journalist, activist, and author.

H.N. Brailsford studied classics and philosophy at the University of Glasgow, where he was a founder of the university’s Fabian Society. Brailsford went on to become a prolific journalist and activist. With another humanist (and Vice President of the Ethical Union), Laurence Housman, he was a founding member of the Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage in 1907. As well as a President of the Ethical Union, Brailsford was an Honorary Associate of the Rationalist Press Association.

Read more about H.N. Brailsford.

Sir Richard Gregory (1864–1952), writer on, and promoter of, science.

The virtues which should be prized most to-day, if civilization is to mean the evolution of social ethics to a nobler plane, is regard for justice, love of truth and beauty, righteousness, care for the suffering, sympathy with the oppressed, and belief in the brotherhood of man.

Richard Gregory, ‘Science and Social Ethics’ in The Rationalist Annual (1940)

Richard Arman Gregory was born in Bristol, the son of John Gregory – an active socialist known as the ‘poet cobbler’. Although he left school at 12, Gregory took evening classes and was ultimately awarded a scholarship to the Normal School of Science, South Kensington in 1885, where he met H. G. Wells. Gregory began to write for the journal Nature in 1889, becoming assistant editor in 1893, and editor in 1919. He also published a series of textbooks, and was Macmillans’ scientific editor for 34 years from 1905. In 1916, Gregory published the popular Discovery, or, The Spirit and Service of Science, epitomising a lifelong devotion to the communication and application of science and the scientific method. Gregory was an Honorary Associate of the Rationalist Press Association, and delivered the 1943 Conway Memorial Lecture at Conway Hall on ‘Education in World Ethics and Science’.

Robert Samuel Theodore Chorley (1895–1978), legal scholar, public servant, and politician.

Lord Chorley was a lawyer, conservationist, and active humanist, who was a prominent figure in the Rationalist Press Association, as well as the Ethical Union. Other positions occupied by Chorley over the course of a long career give an indication of the breadth of his practical humanitarianism, and of his wide-ranging interests. He was: Vice President of the Howard League for Penal Reform; Chairman of the Institute for the Study and Treatment of Delinquency (and later its President); President of the Haldane Society of Socialist Lawyers; and President of the National Council for the Abolition of the Death Penalty. He was also President of the Fell Rock Climbing Club of the English Lake District (1935–7), Vice Chairman of the National Trust; Honorary secretary for the Council for the Preservation of Rural England, President of the British Mountaineering Council, and Vice President of the Alpine Club.

Morris Ginsberg (1889–1970), sociologist and philosopher.

During many years he had carried the burden of sociology in this country almost alone. What the subject has of rigour, order, clarity, scholarship, creative doubt and humane concern in 1970 is the legacy, above all of Ginsberg.

Donald G. MacRae in ‘Morris Ginsberg: An Obituary’, LSE Magazine (December 1970)

Born in Lithuania, Morris Ginsberg excelled first in philosophy (which he studied at UCL), but ultimately left his greatest impression in the field of sociology. In 1914, he became an assistant to L.T. Hobhouse at the London School of Economics (LSE), succeeding him as chair of sociology in 1929. Ginsberg’s enduring interest was in morality – a subject on which he published widely. His books included Moral Progress (1944), The Idea of Progress: a Revaluation (1953), On the Diversity of Morals (1953), and Reason and Unreason in Society (1947). The second of these also formed a chapter in 1968’s The Humanist Outlook, edited by A.J. Ayer. Like so many other presidents of the Ethical Union, Ginsberg was also an Honorary Associate of the Rationalist Press Association. In his entry for the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Ginsberg is described as having been ‘respected for his integrity, loved for his gentleness, and admired for his informed intellectual power.’

[UNESCO’s] main concern is with peace and security and with human welfare… Accordingly its outlook must, it seems, be based on some form of humanism. Further, that humanism must clearly be a world humanism, both in the sense of seeking to bring in all the peoples of the world, and of treating all peoples and all individuals… as equals in terms of human dignity, mutual respect, and educational opportunity.

Julian Huxley, UNESCO: Its Purpose and Its Philosophy (1946)

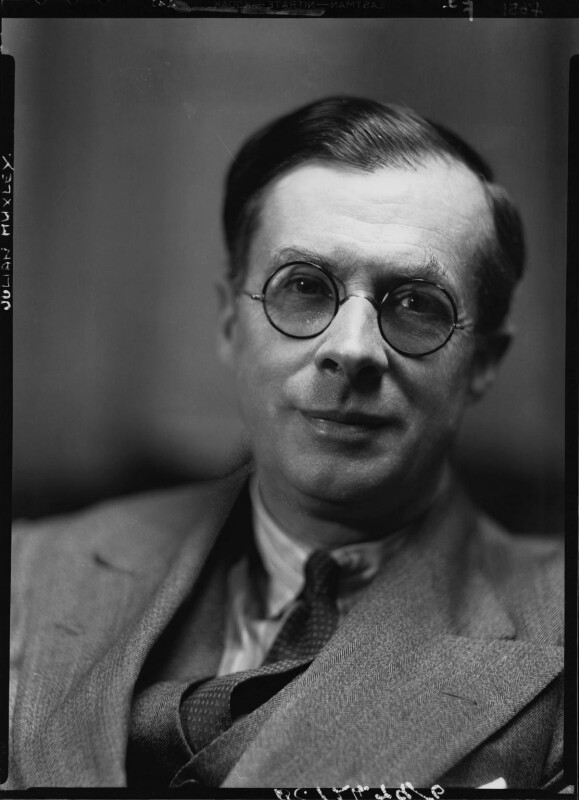

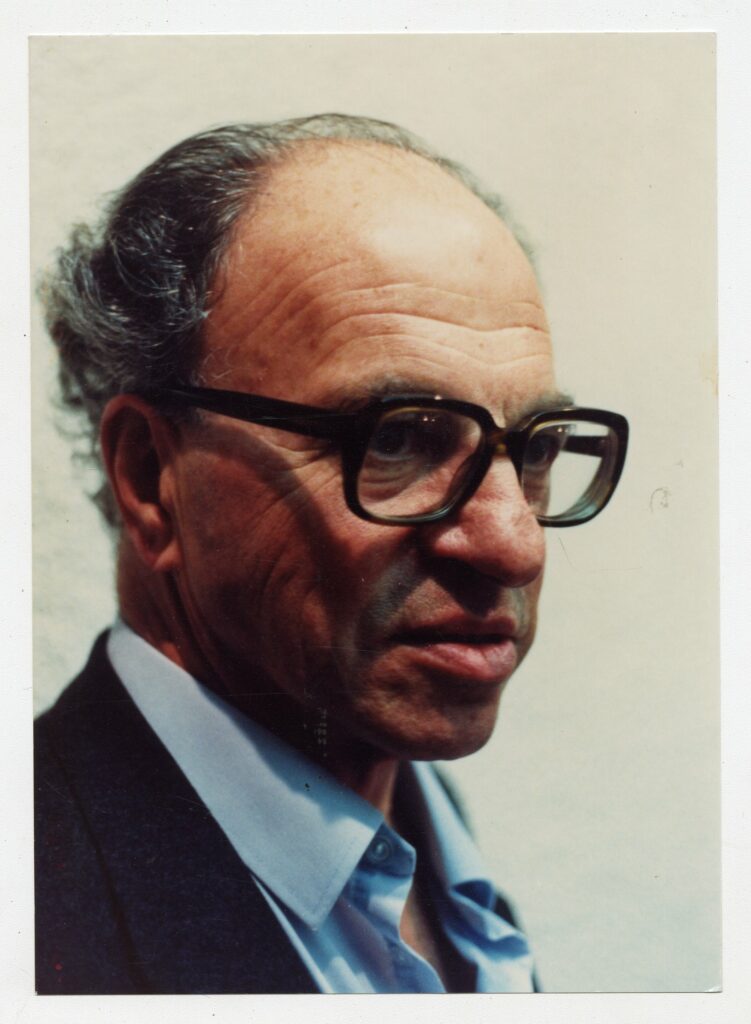

Julian Huxley (1887–1975), zoologist and philosopher.

The son of Leonard Huxley and Julia Arnold, and grandson of T.H. Huxley, Julian came from a long line of powerful intellects, and influential freethinkers. The founding Director General of UNESCO, Julian Huxley was a significant proponent of humanism as a complete, coherent philosophy for living. When, in 1961, he published The Humanist Frame, he described it as:

…the natural outcome of a long process of gestation and development, begun more than half a century ago in an attempt to reconcile or integrate the various aspects of my life – my biological training, my twin loves of nature and poetry, my wrestlings with the problem of morality and belief…

This edited collection set ‘human knowledge worked over by human imagination’ as ‘the basis of human understanding and belief, and the ultimate guide to human progress.’ Its contributors included many of the most influential humanists of the decade, among them H.J. Blackham, Stephen Spender, Jacob Bronowski, and Barbara Wootton.

Read more about Julian Huxley.

In common with other humanists, I believe that the only possible basis for a sound morality is mutual tolerance and respect: tolerance of one another’s customs and opinions; respect for one another’s rights and feelings; awareness of one another’s needs.

A.J. Ayer, introduction to The Humanist Outlook (1968)

A.J. Ayer (1910–1989), philosopher and activist.

Alfred Jules Ayer (known as Freddie to his friends) was a philosopher and activist, Chairman of the Campaign Against Racial Discrimination in Sport, and President of the Homosexual Law Reform Society. He was an Honorary Associate of the Rationalist Press Association from 1947 until his death, and in 1965 became the first President of the Agnostics’ Adoption Society. In 1968, Ayer edited The Humanist Outlook, a collection of essays on the meaning of humanism, to which many of the era’s most prominent humanists contributed.

Read more about A.J. Ayer.

Evolutionary humanism is a total attitude to the human situation; it is not just a nice job lot of Christian-sounding moral precepts.

Edmund Leach, postscript to A Runaway World (1968)

Edmund Leach (1910–1989), social anthropologist.

Edmund Leach was a social anthropologist, described by The Times as ‘one of the most scholarly and original minds in modern social anthropology’. Leach was also an eloquent humanist: an Honorary Associate of the Rationalist Press Association, as well as President of the British Humanist Association, and President of the Royal Anthropological Institute. In 1967, Leach delivered the BBC Reith Lectures, in which he made a case for ‘evolutionary humanism’ as a basis for understanding the role and responsibilities of human beings in the world. In his final lecture, ‘Only connect…’ (taking his title from the ‘magic phrase’ of his fellow humanist E.M. Forster), Leach urged his listeners to ‘keep on remembering the total interconnectedness of things’. ‘The unique and astonishing thing about human beings,’ he suggested:

is not simply their capacity to observe and analyse the contents of the world around them, but their capacity to create. Every one of us is an artist with words. We create brand new sentences, we don’t just imitate old ones. And, as you speak, you generate consciousness; what you create is yourself.

George Melly (1926–2007), writer and singer.

As an almost life-long atheist myself, I find it reassuring to come across others.

George Melly, Slowing Down (2007)

George Melly was a jazz singer and entertainer, as well as the author of books and criticism. Melly delighted in provocation and playfulness, but his ‘deliberately outrageous tone’, wrote Philip Hoare, ‘enhanced rather than concealed his essentially humane and affectionate personality’. Melly appeared in the BHA’s 1992 film The Great Human Detective Story, noting that in the absence of a god to hand out good or bad marks at the end of life, ‘we must just do the best we can’.

Read more about George Melly.

The single theme of humanism is self-determination, for persons, for groups and societies, for mankind together… Humanism is a certain kind of attachment to the world and a certain manner of participation in it.

H.J. Blackham, Humanism (1968)

Harold John Blackham (1903–2009), philosopher, author, and educationist.

H.J. Blackham is remembered as the architect of the contemporary humanist movement in the UK, and began his career in the Ethical movement working for Stanton Coit in the ‘Ethical Church’. He went on to become the first Executive Director of the British Humanist Association, having also been – in 1952 – instrumental in the creation of the International Humanist and Ethical Union (now Humanists International). Blackham’s extensive lecturing, writing, and advocacy helped to define humanism as a firm and full stance for living, as well as to situate the modern movement within a rich tradition of humanist thought, stretching back as far as written records. In Humanism, published in 1968, Blackham was clear in stating that ‘humanism is not religion but it is more than ‘morals without religion’.’ Rather, he wrote, ‘humanism is a concern to understand and to change the world so that human life is more valuable to more people’.

Read more about H.J. Blackham.

James Hemming (1909–2007), psychologist and educationist.

We who are living now are the hope of all who come after us. By taking hold on life with all that is in us of energy, intelligence, imagination, compassion, and delight, we can find our personal fulfilment and create a better tomorrow. We are the inheritors and the creators. The richness comes from living in that truth. The morality comes from the principles that such living involves.

James Hemming, Individual Morality (1969)

James Hemming was a psychologist, educationist, and prominent humanist, who championed the values of dialogue, cooperation, and compassion which remain central to the work of Humanists UK today. A passionate advocate of moral and civic education, Hemming was also active in promoting rational, compassionate attitudes towards sex and sex education. As well as President of the British Humanist Association, Hemming was a Vice President of the Gay and Lesbian Humanist Association (now LGBT Humanists), and of the Campaign for Homosexual Equality. Always committed to the idea of active citizenship and personal responsibility, Hemming proffered ‘Caring, Cooperation, and Cosmic Responsibility’ as a humanist slogan, emphasising our special duties as human beings to one another, and to the world itself.

Read more about James Hemming.

I quote Thomas Paine: ‘We live to improve’, he said, ‘or we live in vain’. I am not quite clear from the context whether he means improving the world we live in or improving ourselves, indeed I am not at all sure he distinguished between the two. ‘We live to improve or we live in vain’, is a very wise saying. It is in service to others, it is as members of the community, that our existence lies.

Hermann Bondi, Humanism – the only valid foundation of ethics (1992)

Hermann Bondi (1919–2005), mathematician and cosmologist.

The longest-serving President of Humanists UK, one of Hermann Bondi’s first initiatives in the role was to call together the Advisory Council and Executive Committee to discuss ‘means of making humanism more visible in society’. By the end of that decade, Bondi could introduce the annual report for 1989 by writing of the dramatic increase in requests for humanist ceremonies, and of the growing support for the British Humanist Association’s efforts to assist society in becoming ‘more united, more driven by the conscience of its members, [and] more tolerant.’ That year, Bondi was awarded the G.D. Birla International Award for Outstanding Contribution to Humanism, presented to him by the then Vice President of India Shankar Dayal Sharma. As epitomised by the title of his 1992 Conway Memorial Lecture, Humanism – the only valid foundation of ethics, Bondi was an influential advocate of humanism as a complete life stance, and devoted to the progress of the organised movement. In 1991, he wrote: ‘One of the great features of the BHA is that the work we need to do never grows less.’

Read more about Hermann Bondi.

Now, there is no difficulty in being good without having a god, if you actually believe that human beings are worthwhile creatures. And if you actually believe as I do, very strongly, that people can be good just for the sheer sake of being good to each other.

Claire Rayner in The Great Human Detective Story (1992)

Claire Rayner (1931–2010), nurse, journalist, broadcaster, and novelist.

Claire Rayner was a beloved agony aunt and author, whose resolutely common sense approach to life and health was allied with humour and humanity. As an advice columnist and journalist, Rayner emphasised compassion and frankness, not least in those areas typically viewed as taboo – from sexual health to sanitary products. As her husband, Des Rayner, recalled: ‘Through her own approach to life she enabled people to talk about their problems in a way that was unique.’ In addition to a prodigious press output, Rayner also published novels and made television appearances, including Claire Rayner’s Casebook for the BBC. As well as an active and eloquent President of the British Humanist Association, Rayner was President of the National Association of Bereavement Counsellors, of Gingerbread (a charity working with single parent families), and of the Patients’ Association. A fervent supporter of the National Health Service, she also championed improved care for the elderly. In 1996, Rayner was awarded the OBE for ‘services to women’s issues and health issues’. Rayner, who began her career as a nurse and had originally intended to train as a doctor, told relatives she wanted her last words to be: ‘Tell David Cameron that if he screws up my beloved NHS I’ll come back and bloody haunt him.’

Read more about Claire Rayner.

I only found out that the beliefs I hold are ‘humanistic’ when the BHA kindly invited me to be its president. I am sure that I’m typical of many unconscious humanists. I see publicising humanism in order that other people might identify themselves, not just negatively as atheists but positively as humanists, as a vital part of my role.

Linda Smith on becoming President of the British Humanist Association in 2004

Linda Smith (1958–2006), comedian and broadcaster.

Born in Erith, Kent, Linda Smith’s career began in Sheffield, where she attended university and helped to found Sheffield Popular Productions – producing community theatre and hosting benefit shows in support of the miners’ strike 1984-5. It was in Sheffield she met Warren Lakin, her devoted partner for 23 years, and still a patron of Humanists UK. Her firmly held political beliefs animated Smith throughout her life but, as fellow comedian Jeremy Hardy wrote in an obituary for The Guardian, ‘were never dry nor passionless, nor did they stray into rhetoric. They came from a basic sense of what is decent, fair, sensible and humane.’ After many successful years in stand-up comedy, by the late 1990s Smith had gravitated towards radio, becoming a staple of comedy shows including The News Quiz, Just a Minute, and I’m Sorry I Haven’t a Clue. In 2002, she was voted Wittiest Living Person by Radio 4 listeners, beating Stephen Fry, who would later describe Smith as ‘one of the smartest, funniest and most sweet natured people I ever encountered in the comedy world.’ In 2004, Smith discussed her atheism on Radio 4’s Devout Sceptics, and in that year became President of the British Humanist Association. Smith died from ovarian cancer aged just 48. Since her death, a series of Loving Linda comedy galas have raised thousands of pounds for Target Ovarian Cancer.

Subsequent Presidents of Humanists UK have included columnist and broadcaster Polly Toynbee (2007–12), scientist and author Jim Al Khalili (2013–15), comedian Shaparak Khorsandi (2016–18), and anatomist and author Professor Alice Roberts (2019-2022).

As in the case of other individuals featured on the Humanist Heritage website, inclusion in this list does not imply endorsement of every belief or opinion expressed by that person. For more on this see: Our approach.

Its main concern is with peace and security and with human welfare, in so far as they can be subserved […]

Tony Brierley was an active part of the humanist movement for more than 60 years, and a founder of both […]

The death of Shaw is to progressive people of the twentieth century what the death of Voltaire must have been […]

…no child should be made ashamed or uncomfortable on account of his father’s opinions, or lack of opinions, on subjects […]