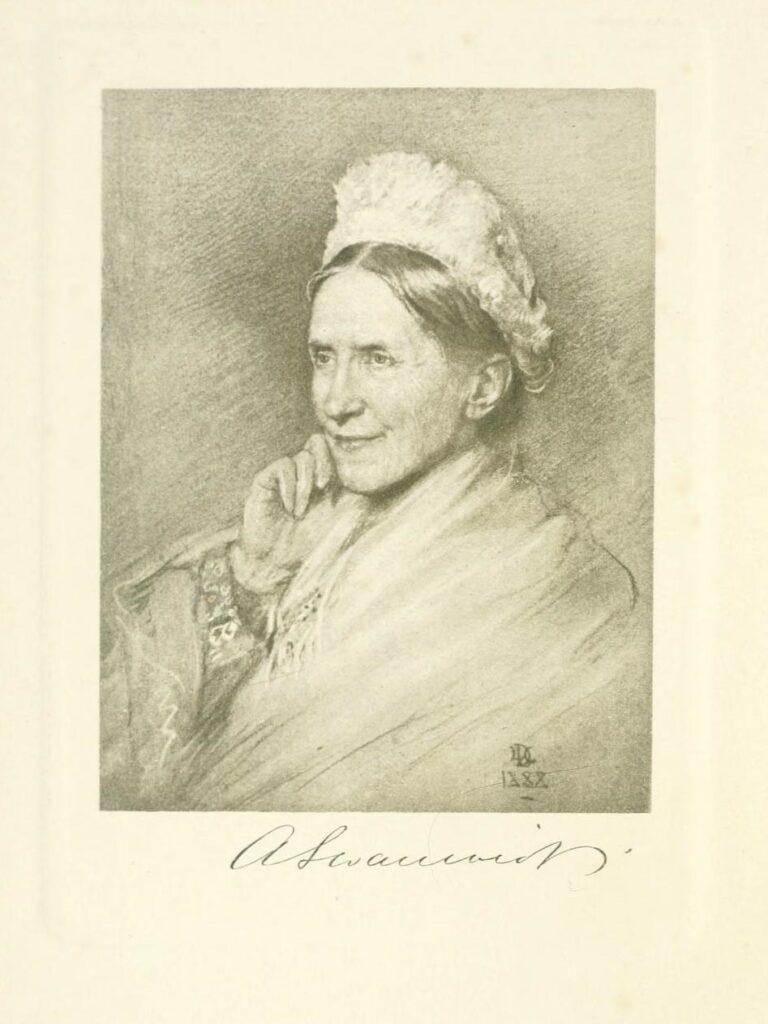

‘Heroines of Freethought’ was the title of an 1876 work by Sara Underwood that celebrated the lives of humanist women who lived and worked before the emergence of humanist organisations such as the ethical societies. Mary Wollstonecraft (1757-1759) and Frances Wright (1795-1852) combined feminism and freethought in writing and lecturing for social reform. Followers of Robert Owen, who lectured widely in the name of socialism and secularism, numbered among them Margaret Chappellsmith (1806-1883), Ernestine Rose (1810-1892), and Emma Martin (1812-1851) – all of whom drew particular ire as outspoken and ‘godless’ women.

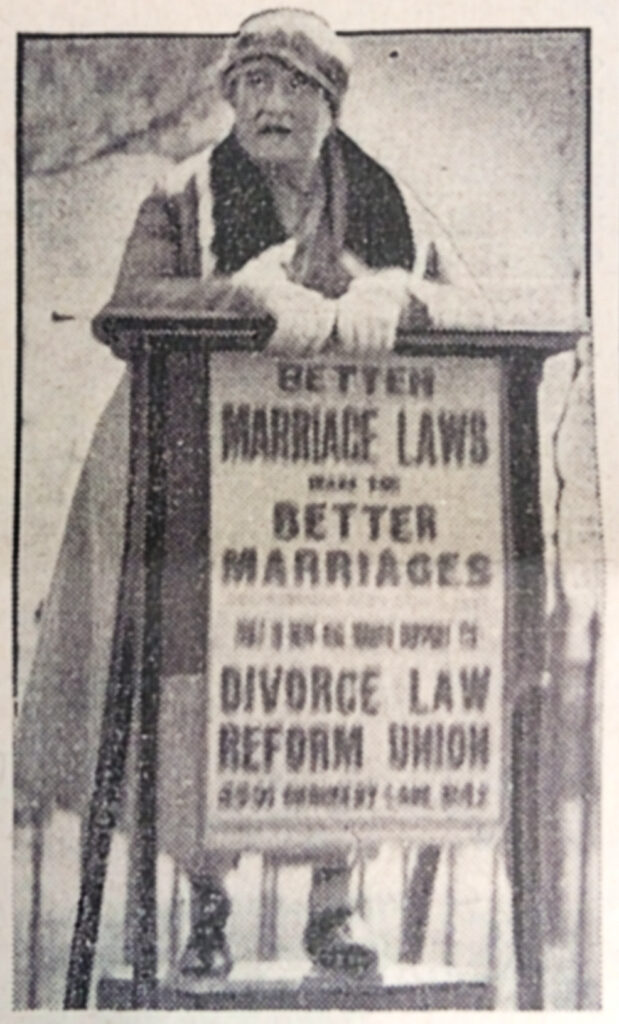

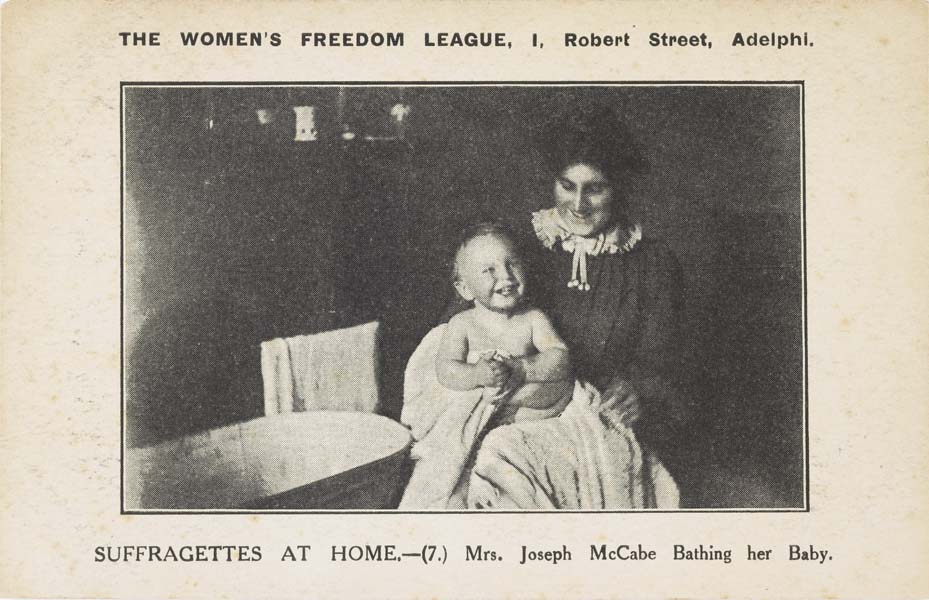

The wave of blasphemy prosecutions in the first half of the 19th century, which famously targeted men like Richard Carlile and George Jacob Holyoake, also saw Matilda Roalfe, Susannah Wright, and Jane and Mary Ann Carlile prosecuted and imprisoned. Eliza Sharples, who became Carlile’s common law wife and took in a young Charles Bradlaugh, also believed passionately in the freedom of speech and belief, enduring poverty and hardship in their pursuit. Later, women like writer, war correspondent, suffragist, and traveller Lady Florence Dixie, further threw off the constraints of Victorian society to advance rational and empathetic reforms in everything from modes of dress to bloodsports. All of these radical freethinkers paved the way for humanist women to come.